Marilyn Rubin is a Distinguished Research Fellow at the Newark School of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University as well as an Academy Fellow.

Michael Walker is a Professor and Chair of the Criminal Justice Department at the Passaic County Community College in Paterson, New Jersey.

Introduction

The criminal justice system in the United States has evolved from English common law into a complex series of procedures and decisions within a system with three levels of government participating: federal, state, and local. This multi-government structure creates a patchwork of policies and procedures that complicate the delivery of criminal justice services throughout the nation.

Setting the Federal Context for the US Criminal Justice System

Under the US Constitution, general policing power is not given to the federal government. Congress has, however, impacted law enforcement with legislation enacted under other constitutional powers such as that provided in the Spending, Commerce, Territorial, and Necessary and Proper Clauses. A notable example of Congressional action related to criminal justice that has impacted today’s criminal justice system is the 1994 Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act that was passed by Congress with bipartisan support, including that of our current president. Among its many provisions, the Act provided funds to local governments to put more cops on the street, imposed tougher prison sentences and provided money for additional prisons. While it was meant to reverse decades of rising crime, the Act is seen by many as driving mass incarceration, especially for people of color.

Several decisions by the Supreme Court have also had a significant impact on today’s criminal justice system. Significant examples include two court decisions that impacted police use of force. In the 1985 Tennessee v. Garner case, the Court ruled that a police officer could shoot only if she/he had a good-faith belief that the suspect posed a significant threat of death or serious bodily injury to the officer or others. Four years later, in Graham v. Connor, the Court ruled that an officer’s use of force must be evaluated under the ‘objectively reasonable’ standard in light of the facts and circumstances confronting the officers at the scene. Among the implications of the Graham v. Connor decision was that an officer’s actions resulting in a suspect’s death may be legal if the officer believed his or her life was at risk. This decision was cited by both the prosecution and defense in the State vs. Derek Chauvin case in 2021 regarding the killing of George Floyd in which police office Chauvin was found guilty.

Components of the US Criminal Justice System

At all levels of US government, the three components of the criminal justice system are policing, courts, and corrections. According to the Urban Institute, in 2018, state and local governments spent $119 billion on police, $81 billion on corrections, and $49 billion on courts.

Policing

Although all three levels of government contribute to paying the costs of policing, it is primarily a state and local function. Each of the 50 states defines its own criminal justice system in its constitution and laws, and delegates authority and responsibilities to local jurisdictions.

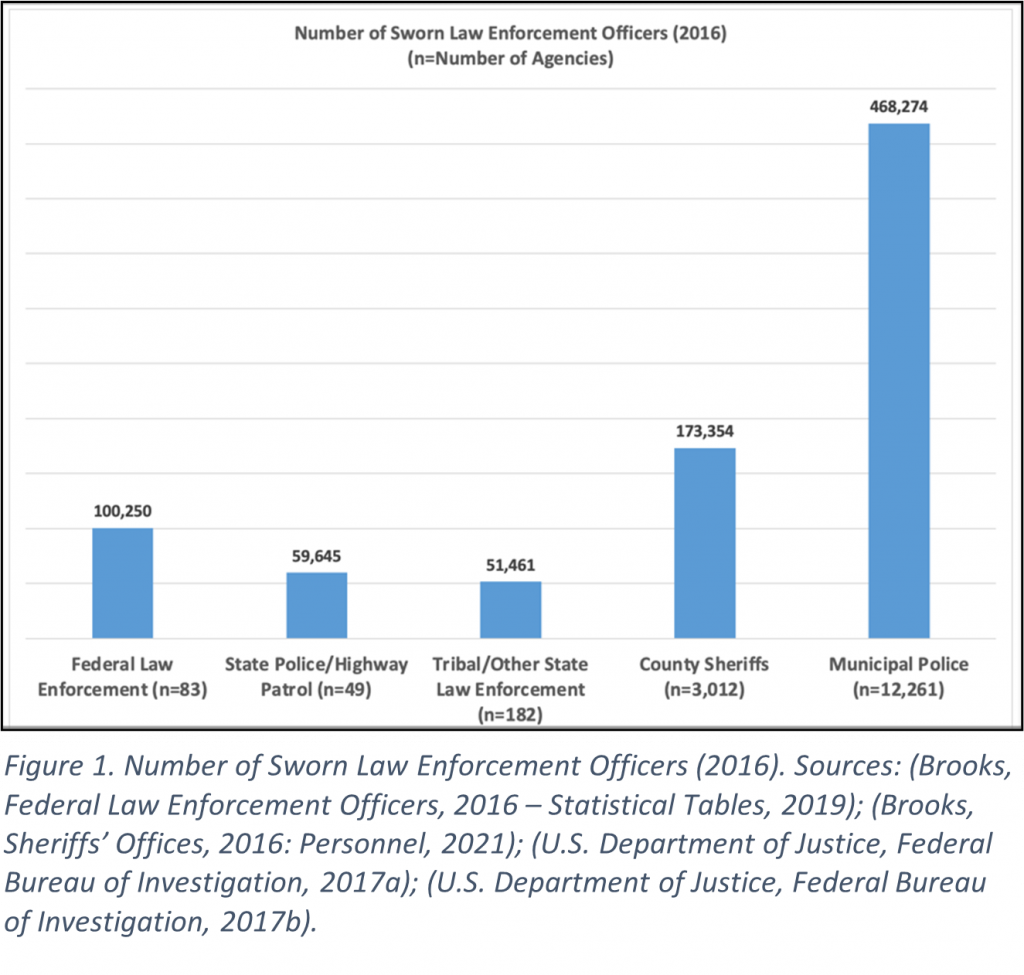

As shown in Figure 1, in 2016, across all levels of government, law enforcement agencies employed more than 800,000 sworn officers, i.e., police officers who are armed and have the power to arrest. Over half of this total were municipal police officers and another 20 percent were county sheriffs. At the county and municipal levels, law enforcement agencies have as few as one sworn officer to as many as 36,000 in New York City.

State governments account for less than 10 percent of all sworn officers in the US. Among the 50 states, 49 have either a state police or highway patrol; Hawaii leaves law enforcement to county and municipal governments. Policing in tribal, (Native American) areas is done through a combination of Bureau of Indian Affairs officers and tribal police officers, or by state or local police.

The federal government employs about 10 percent of all sworn officers, with the Department of Homeland Security accounting for close to half of the 10 percent. Although policing is predominantly a state and local function, the federal government influences policing in several ways including “policing-related data collection…federal processes to investigate local police misconduct, and the relationship between the Department of Justice (DOJ) and police throughout the United States.”

The Criminal Court System

At the federal level, the criminal court system includes district courts that are general trial courts, courts of appeal that are divided into 13 districts that hear appeals from district courts, and the Supreme Court, the court of final jurisdiction. Although many states follow the federal terminology for courts, some have used other names, causing confusion. As an example, in New York, trial courts are called Supreme Courts while the appellate level courts are called Appellate Divisions of the Supreme Court, and the court of final jurisdiction is the Court of Appeals. Thus, the confusion since the Supreme Court is the court of final jurisdiction in the US, but, in New York, it is an intermediate level court.

Corrections

The federal Bureau of Prisons is responsible for prisons that house offenders who have been convicted of federal crimes, such as drug trafficking, identity theft, tax fraud, and child pornography. There are 151,000 inmates in the 122 federal prisons throughout the U.S. In the states, prisons are one of the three components under the “corrections umbrella.” There are more than 1,800 state prisons in the US. housing more than 1.3 million inmates. The other two components under the state corrections umbrella are probation, which is responsible for persons convicted of a crime but not imprisoned, and parole, which oversees persons released from prison before the expiration of their sentences. The federal government provides some funding assistance to state corrections activities, but it is piecemeal across the states.

Federalism Conflicts

Marijuana Legalization

The recent controversy in the 2020 Olympics over the use of marijuana by an elite female runner has brought intergovernmental issues in criminal justice to the forefront. The role of the federal government in the use of marijuana began more than 80 years ago when the Federal Bureau of Narcotics, the predecessor to the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA), petitioned Congress to control the use of marijuana, and Congress responded with the “Marihuana Tax Act of 1937”, effectively criminalizing the cultivation, sale, or possession of marijuana. On the other hand, as of July 2021, 18 states, the District of Columbia, and two US territories have either legalized or decriminalized the use of marijuana by adults; 36 states, the District of Columbia, and 3 US territories allow for the medical use of cannabis products including marijuana.

Because marijuana is illegal under federal law, it cannot be transported across state lines even when it is legal in the sending/receiving states. This leads to a supply and demand problem since some states may have more supply than they need for residents while adjacent states may have demand that exceeds in-state supply. The supply/demand imbalance, along with the prohibition on interstate commerce, also influences the price of marijuana. To illustrate: in 2021, California, where supply has generally met demand, the “average price of an ounce of premium marijuana was about $260” whereas “in New Jersey, the price hovers between $350 and $450 an ounce.” Internet sources during the Summer of 2021 listed the street price of an ounce of marijuana in New Jersey at approximately $300, which contributes to the persistence of a black market despite the legalization of the substance.

Capital Punishment

Among the several other areas of intergovernmental conflict in criminal justice is capital punishment. Although the federal government, US military, and 27 states permit capital punishment, several states have statutorily abolished capital punishment; in some states, the courts have ruled capital punishment to be unconstitutional. The effect of this is that a person committing a murder in one state can, if found guilty, receive the death penalty whereas a person living in another state who has committed the same crime will not, violating the equal protection clause of the Fifth Amendment.

Conclusion

While a less fragmented federal system would allow for more consistent delivery of criminal justice services, it is not unexpected that, the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) “…urges Congress and the Administration to avoid federalizing crime policy and substituting national laws for state and local policy decisions affecting criminal and juvenile justice.” It is also not unexpected that NCSL continues to support the need for federal funding to implement their criminal justice activities. So, the intergovernmental saga continues.

Marilyn M. Rubin is a Distinguished Research Fellow at the Rutgers School of Public Affairs and Administration at Rutgers University. She spent 30 years as a Professor of Public Administration and Economics and Director of the MPA Program at John Jay College of the City University of New York (CUNY). She also has more than 35 years of experience working as a

consultant and advisor to high-level government officials in the U.S. and abroad on projects related to economic development, fiscal policy, gender budgeting, and strategic planning.

Michael C. Walker is a Professor and Chair of the Criminal Justice Department at the Passaic County Community College in Paterson, New Jersey. He spent 32 years as a police officer in the City of Paterson, attaining the rank of Captain before serving as the City’s Police Director. He holds a Master of Public Administration Degree from the City University of New York’s John Jay College of Criminal Justice in Criminal Justice Policy. He is a graduate of the FBI National Academy and serves as a member of the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reporting Subcommittee.